New Old Men and Old New Men: The Ebb and Flow

of Patriarchal Pull in Sweet Sixties and When I Turned Nine

by Adam Hartzell

The obvious connection between the South Korean films Sweet Sixties (Lee Su-in, 2004) and When I Turned Nine (Yun In-ho, 2004) is the fact that the young actress Lee Su-yeong is in both.(1) There are other connections. Both films take place well outside of Seoul, and both plots revolve around a mysterious female character from Seoul settling for a spell in their respective towns. Yet, all these connections are irrelevant when we consider the drastic differences between the political directions of these two films. Whereas Sweet Sixties poses alternatives to patriarchal precepts including a Queer-friendly subplot, When I Turned Nine advocates regular reinforcement of core patriarchal principles, primary of which is that women require, and thus should submit to, male protection.

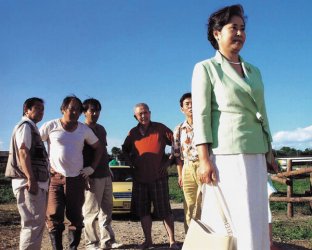

In-ju (Sunwoo Yong-rye) is the mysterious woman who enters the fishing port town of Sweet Sixties. Recently divorced, she arrives in this town to claim an island her ex-husband signed over to her as part of his alimony. This "island" ends up merely being a rock jutting out of the bay. In-ju is in her 60's, as is the majority of

players in this romantic comedy, hence the English title of the film.(2)

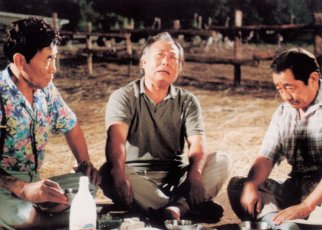

In-ju's presence in this port town rouses the interest of many of the 60-year-old

fellows, most intensely Pil-guk (Song Jae-ho) and Jin-bong (the late Kim Mu-saeng)(3), the former a fisherman and the latter a retiree who remains a

virulent anti-communist. Jin-bong's arch-rival is Joong-dal (Joo Hyun). This rivalry does not exist because Joong-dal also seeks In-ju's affections. Joong-dal is too concerned in meeting his elder brother duties of marrying off his younger brother, Joong-bum (Park Young-gyu), who, appearing as if in his late 40s, has still yet to marry. Their dispute with each other is primarily around property. Joong-dal has recently put up an ostrich farm, much to the chagrin of his nextdoor neighbor, Jin-bong.

In-ju's presence in this port town rouses the interest of many of the 60-year-old

fellows, most intensely Pil-guk (Song Jae-ho) and Jin-bong (the late Kim Mu-saeng)(3), the former a fisherman and the latter a retiree who remains a

virulent anti-communist. Jin-bong's arch-rival is Joong-dal (Joo Hyun). This rivalry does not exist because Joong-dal also seeks In-ju's affections. Joong-dal is too concerned in meeting his elder brother duties of marrying off his younger brother, Joong-bum (Park Young-gyu), who, appearing as if in his late 40s, has still yet to marry. Their dispute with each other is primarily around property. Joong-dal has recently put up an ostrich farm, much to the chagrin of his nextdoor neighbor, Jin-bong.

There are three primary plots nestled within Sweet Sixties. The first centers around which suitor In-ju will choose, the second why Joong-bum has yet to be betrothed, and the third what Jin-bong's secret is. Each plot's resolution supports a progressive view, negating conservative traditions about how men should be.

We learn of In-ju's choice through a moment of subtle dialogue. Guiding Pil-guk out so they will be alone, In-ju indirectly drops a playful proposition by asking about Youn-hee, Pil-guk's granddaughter (played by the young actress I mentioned in the first paragraph, Lee Su-yeong) of whom he is the sole caretaker. "Youn-hee is probably asleep, you think?" Unfortunately, Pil-guk the fisherman doesn't catch the bait offered him, which is consistent with his character. And it is his character's disposition that challenges patriarchal posturings. Pil-guk is almost meek in his quiet demeanor, often looking away in In-ju's presence, as if he is the schoolgirl and not his granddaughter. In fact, it is his granddaughter who gives him some pointers, "Take a bath if you have the time. You stink." Pil-guk almost appears to shuffle along, never strutting like a rooster with patriarchal pride, such as Jin-bong does. If he takes pride in anything, it's his care for Youn-hee, as if liberated from patriarchal precepts through his grand-fatherhood, such as when he engages in the unmanly act of braiding her hair. The mere fact that In-ju chooses Pil-guk over the chest-thrusting, masculine poses of Jin-bong presents a redefinition of what type of men can be desired by women in this port town, a region that we find cinema often typecasting as the last bastions of hardcore masculinity.

As for Joong-bum's perpetual bachelorhood, we learn that his single-hood, if not voluntary, is at least adaptive. When we follow Joong-bum to a karaoke bar, where Joong-bum's humorous tone-deaf singing(4) symbolizes his emotional anguish, we quickly surmise that this isn't just any karaoke bar. By quickly surveying the bar and noting none of the familiar signifiers of bars for men we've come to expect in Korean films - the short-skirted, tight-fitting uniforms of garishly made-up bar hostesses who would be faux-fawning over their clients as they pour them soju -- we notice men embracing in the unfocused background. We quickly realize we are in a Gay bar. And we realize we are in Joong-bum's sanctuary from the patriarchal protocols that would require him to be married with children by now. Although this appears to be news to everyone when finally announced, eventually his friends and family accept him.

As for Joong-bum's perpetual bachelorhood, we learn that his single-hood, if not voluntary, is at least adaptive. When we follow Joong-bum to a karaoke bar, where Joong-bum's humorous tone-deaf singing(4) symbolizes his emotional anguish, we quickly surmise that this isn't just any karaoke bar. By quickly surveying the bar and noting none of the familiar signifiers of bars for men we've come to expect in Korean films - the short-skirted, tight-fitting uniforms of garishly made-up bar hostesses who would be faux-fawning over their clients as they pour them soju -- we notice men embracing in the unfocused background. We quickly realize we are in a Gay bar. And we realize we are in Joong-bum's sanctuary from the patriarchal protocols that would require him to be married with children by now. Although this appears to be news to everyone when finally announced, eventually his friends and family accept him.

In the constricting views of manhood that patriarchy requires, Gay men have no place other than as an example of emasculation. (Lesbians have a place, but only in the orgies of patriarchal minds.) Their mere existence, their intimate desires, their free choices, each challenges the patriarchy's constrained definition of strength, the patriarchy's limited ideas about what constitutes family and a man's role in it. The eventual embrace of Joong-bum by his family and friends, an embrace that includes his lover, restructures the masculine in this port town, limiting the influence of any patriarchal commands.

And the patriarchy is further torn down by the treatment of Jin-bong. Interestingly, when considering the anti-communism required by Korean films produced under President Park Chung-hee's regime(5), the treatment of Jin-bong's anti-communist stance is quite astonishing. Not one character in this film likes Jin-bong, making it difficult for the audience to sympathize with Jin-bong. In-ju tolerates him initially since she realizes she is an outsider in this port town, but she eventually displays complete disinterest in Jin-bong and does not find his anti-communist credentials and

patriarchal claims impressive. Jin-bong introduces himself to In-ju through the Korean custom of presenting a business card. In-ju looks away when receiving the card as appropriate within the ritual. However, this ritual is disrupted by Mi-seon (Jin Hee-kyun), the younger proprietor of the town's only inn, who swipes the card from its intended recipient, laughing at the outlandishly pompous titles Jin-bong has awarded himself, "Director of the Extermination of Harmful Birds Association" and "Region Leader of the Anti-Communist Lee Seung-bok Organization." In a later meeting between Jin-bong and In-ju, Jin-bong actually labels Joong-dal a communist because he refers to the late President Park Chung-hee as just "Park Chung-hee", without the "President" title. Rather than find such demeanor impressive, In-ju pays more attention to the embarrassing fact that Jin-bong has his clothes on inside out, humiliating Jin-bong by pointing this out to him. Further ridicule will occur over Jin-bong's clothing when we learn, through a trip to the emergency room, that he is the one who has been stealing women's underwear throughout the town's private clotheslines. Jin-bong's secret, it turns out, is that he likes to wear women's underwear. And such proclivities are why he was kicked out of his son's home, kicked from his place of reverence to return to the port town against his will. His less-than-manly clothes worn underneath partly explain his signifiers of fiery Anti-communism and trophies of wild birds as masculine compensation for his inability to uphold unattainable patriarchal principles. His multiple masculine masks are merely meant to hide vulnerability underneath.

patriarchal claims impressive. Jin-bong introduces himself to In-ju through the Korean custom of presenting a business card. In-ju looks away when receiving the card as appropriate within the ritual. However, this ritual is disrupted by Mi-seon (Jin Hee-kyun), the younger proprietor of the town's only inn, who swipes the card from its intended recipient, laughing at the outlandishly pompous titles Jin-bong has awarded himself, "Director of the Extermination of Harmful Birds Association" and "Region Leader of the Anti-Communist Lee Seung-bok Organization." In a later meeting between Jin-bong and In-ju, Jin-bong actually labels Joong-dal a communist because he refers to the late President Park Chung-hee as just "Park Chung-hee", without the "President" title. Rather than find such demeanor impressive, In-ju pays more attention to the embarrassing fact that Jin-bong has his clothes on inside out, humiliating Jin-bong by pointing this out to him. Further ridicule will occur over Jin-bong's clothing when we learn, through a trip to the emergency room, that he is the one who has been stealing women's underwear throughout the town's private clotheslines. Jin-bong's secret, it turns out, is that he likes to wear women's underwear. And such proclivities are why he was kicked out of his son's home, kicked from his place of reverence to return to the port town against his will. His less-than-manly clothes worn underneath partly explain his signifiers of fiery Anti-communism and trophies of wild birds as masculine compensation for his inability to uphold unattainable patriarchal principles. His multiple masculine masks are merely meant to hide vulnerability underneath.

The most direct scene de-throning Jin-bong's anti-communism involves dialogue between a teacher and one of the boys in the town. Jin-bong takes it upon himself to clean the statue of Lee Seung-bok, an immortalized anti-communist figure that rests in front of the town's school.(6) Looking out the window and seeing Jin-bong religiously engaged in his daily ritual, the little boy says to his teacher that such a sight makes him sad not in relation to Jin-bong, but in relation to the statue. "Would you like it if that Grandpa wiped you everyday?" The teacher's silent facial gesture implies that he agrees with the young boy. Jin-bong's efforts to connect himself with the greatness inscribed in Korean anti-communist history are severed by the boy's 'out of the mouths of babes' commentary, pushing this man who thinks he's king of the masculine off from his self-designated pedastal. Since patriarchy is closely tied to nationalistic portrayals of patriotism, and since South Korean modern nationalistic expression of patriotism is tightly connected with a history privileging anti-communism, this act fully signifies this film's efforts to destabilize patriarchy, and expand wider possibilities of what men can and can't be.

The casting of Sweet Sixties adds yet another level to the progressive direction taken with this film. All the older actors and actresses performed in films from the 70's and 80's. Although two decades not known as the best for Korean Cinema, these actors and actresses are some of South Korea's most revered older actors, particularly Joo Hyun and Song Jae-ho. As was mentioned before, the 70's and early 80's were a time of intense nationalism of the sort espoused by the character Jin-bong, requiring an entwining of masculinity with patriotism as the height of a patriarchal worldview. And such a worldview was required in the films produced while President Park Chung-hee was in office. By accident of birth, these actors originally had no choice but to take on characters that presented such a patriarchal view if they wanted to act at all. Allowing them to expand on their repertoire of masculine avenues here in Sweet Sixties adds yet another layer to the progressive direction this film advocates. And it is quite ironic that these New Men of the 21st Century are portrayed for us by Old Men of the 20th Century.

The casting of Sweet Sixties adds yet another level to the progressive direction taken with this film. All the older actors and actresses performed in films from the 70's and 80's. Although two decades not known as the best for Korean Cinema, these actors and actresses are some of South Korea's most revered older actors, particularly Joo Hyun and Song Jae-ho. As was mentioned before, the 70's and early 80's were a time of intense nationalism of the sort espoused by the character Jin-bong, requiring an entwining of masculinity with patriotism as the height of a patriarchal worldview. And such a worldview was required in the films produced while President Park Chung-hee was in office. By accident of birth, these actors originally had no choice but to take on characters that presented such a patriarchal view if they wanted to act at all. Allowing them to expand on their repertoire of masculine avenues here in Sweet Sixties adds yet another layer to the progressive direction this film advocates. And it is quite ironic that these New Men of the 21st Century are portrayed for us by Old Men of the 20th Century.

However, what a difference half a century sometimes does not make, because any inroads made by such a progressive take on manhood were quickly challenged by When I Turned Nine, a film released the week following the release of Sweet Sixties.(7) When I Turned Nine advocates for the return to patriarchal tenets in the main character's adoption of lessons learned from his father, tenets reinforced in scene after scene within the film. This main character is nine-year-old Yeo-min (Kim Seok), a third-grader who takes care of bullies at his school, even bullies all the way up to fifth-grade. His friends Ki-jong (Kim Myeong-ja) and Keum-bok (Na Ah-hyun) desire Yeo-min as their leader, and Keum-bok desires him a little bit more than that, having a crush on Yeo-min that rises to the surface when her privileged ties to Yeo-min are challenged by Woo-rim's (Lee Su-yeong, again) arrival in the town. Based on the best-selling novel of the same name by We Ki-chul, the film sets up multiple scenes that reinforce a definition of manhood more inclined with patriarchy.

Yeo-min vocalizes his full conscription into the patriarchy through his announcements that his father is his model of manhood. "My dad always said men have to protect women, no matter what." And the few scenes that involve his father (Ji Dae-han) underscore this. We begin the film with father dutifully leaving for work while his wife and two children obediently see him off with smiles of adoration for all he does for them. Much later we see him bring water to a woman whom, through the knowledge network of town gossip, he knows has a difficult time making ends meet since her husband is an alcoholic, sleeping all day in order to drink all night rather than providing for his family. Yet these efforts anger this woman's abusive husband. This gossip travels to Yeo-min's mother (Jeong Seon-kyung) who asks her husband to stop delivering water to this woman because she's worried her husband's efforts might incite further abusive behavior by the woman's husband. As far as we know, Yeo-min's father does abide by Yeo-min's mother's wishes. This compliance to his wife's wishes, along with the fact that the father, as caring nurturer, never enacts any corporeal punishment upon the family, allows for a completely admirable view of the father. And, until the rest of the film is brought into context, this is not necessarily a regressive view either.

Yeo-min vocalizes his full conscription into the patriarchy through his announcements that his father is his model of manhood. "My dad always said men have to protect women, no matter what." And the few scenes that involve his father (Ji Dae-han) underscore this. We begin the film with father dutifully leaving for work while his wife and two children obediently see him off with smiles of adoration for all he does for them. Much later we see him bring water to a woman whom, through the knowledge network of town gossip, he knows has a difficult time making ends meet since her husband is an alcoholic, sleeping all day in order to drink all night rather than providing for his family. Yet these efforts anger this woman's abusive husband. This gossip travels to Yeo-min's mother (Jeong Seon-kyung) who asks her husband to stop delivering water to this woman because she's worried her husband's efforts might incite further abusive behavior by the woman's husband. As far as we know, Yeo-min's father does abide by Yeo-min's mother's wishes. This compliance to his wife's wishes, along with the fact that the father, as caring nurturer, never enacts any corporeal punishment upon the family, allows for a completely admirable view of the father. And, until the rest of the film is brought into context, this is not necessarily a regressive view either.

Yet regressive views surrounding gender roles do dominate. In the most interesting scene involving the father, Yeo-min helps him patch up the roof of the house while it is pouring rain. The mother is quite concerned, making several calls to "Be careful!" while they mend the roof and telling Yeo-min to "Watch your steps!" as he comes down from the roof. Neither Yeo-min or his father slips or falls, each safely coming down from the roof. However, it is the mother who in fact should have heeded her own advice to "be careful" because when she enters the house before them, she smacks her head hard to the point of drawing blood. As the father holds her, he exclaims "I told you to be more careful. Remember what happened last time." This comment is not made with a tone of 'I told you so', but out of genuine concern for her safety. Still, the comment further reinforces how men know better and must protect women.(8)

Yeo-min himself is portrayed as a noble leader, someone who will only fight when another's honor is threatened. The grade school is portrayed sociologically as a prison where each child must find their "leader" to protect them amongst the bullies positioning for power. When he beats up his first challenger, he does so as a fighter with superior morals, telling his defeated challenger, "I won't tell anyone that I beat you only if you promise not to call my friends by those nicknames. Got it?" Later, he refuses to fight the new bully in town because he has no beef with him personally, and because Woo-rim tells him not to. He only chooses to pummel the new bully when the bully makes a derogatory comment about his mother. To further protect his mother, he takes on odd jobs to earn enough money to purchase sunglasses for her so she can cover her eyes from the stares of the public. In fact, Yeo-min's most violent action is that against the disapproving gaze of a shop-owner who will not allow Yeo-min's mother to purchase shoes because of her disability. Seeking revenge, Yeo-min smashes the shop-owner's window with a brick. Like Yeo-min's knocking out of the new bully, this violence is presented to us as justified in order to retain his mother's honor.

Yeo-min himself is portrayed as a noble leader, someone who will only fight when another's honor is threatened. The grade school is portrayed sociologically as a prison where each child must find their "leader" to protect them amongst the bullies positioning for power. When he beats up his first challenger, he does so as a fighter with superior morals, telling his defeated challenger, "I won't tell anyone that I beat you only if you promise not to call my friends by those nicknames. Got it?" Later, he refuses to fight the new bully in town because he has no beef with him personally, and because Woo-rim tells him not to. He only chooses to pummel the new bully when the bully makes a derogatory comment about his mother. To further protect his mother, he takes on odd jobs to earn enough money to purchase sunglasses for her so she can cover her eyes from the stares of the public. In fact, Yeo-min's most violent action is that against the disapproving gaze of a shop-owner who will not allow Yeo-min's mother to purchase shoes because of her disability. Seeking revenge, Yeo-min smashes the shop-owner's window with a brick. Like Yeo-min's knocking out of the new bully, this violence is presented to us as justified in order to retain his mother's honor.

Yeo-min also oversees the protection of the girls at his school. He scolds fellow classmates for harassing girls on the playground. He intervenes on Woo-rim's behalf so her secret is not exposed. And epitomizing his protection of Woo-rim, we even have Yeo-min saving Woo-rim from drowning, an obligatory melodramatic trope of such cliche-d proportions even the most cynical will be surprised to see such a scene resurface here along with both Woo-rim and Yeo-min's unconscious bodies.

Equally important to the plot is a Poet who uses Yeo-min as an intermediary to take poems he has written to the woman with whom he is obsessed. Initially, Yeo-min follows the Poet's lead and anonymously confesses his feelings to Woo-rim. Woo-rim, however, knows the note is from Yeo-min and proceeds to embarrass him in class, as if to punish him for not being man enough and owning up to his feelings publicly, instead hiding behind weak words. As go-between for the Poet and his muse, Yeo-min learns that it is action that defines the man. The object of the Poet's obsession takes a liking to Yeo-min, and Yeo-min learns that she does not take a liking to the Poet due to his passivity and irresponsibility. Yeo-min shows he's learned that this Poet represents the opposite of what a man should be by acting on his feelings for Woo-rim the night before Woo-rim is to return to Seoul. And this action is to steal a kiss from her. Since the film identifies Yeo-min as possessing artistic talent himself, we have the emerging manly command of Yeo-min as artist juxtaposed with the impotent artist of the Poet.

The positioning of Woo-rim also contributes to When I Turned Nine's repositioning of patriarchy. Woo-rim has been lying to her new classmates that her father lives in America, from where he buys her many gifts. This is the secret that Yeo-min is aware of through Keum-bok's sleuthing. Yeo-min, as leader, asks Keum-bok to refrain from exposing this secret as a favor to him because he feels Woo-rim has her reasons for telling these lies and he doesn't want Keum-bok to embarrass her. Keum-bok, in the heat of anger and jealousy, does end up exposing Woo-rim's lies to the class. But Woo-rim does eventually fess up publicly on her own to her classmates in a horribly overly melodramatic scene. This confessional has the whole school crying because Woo-rim is a child of divorce and that appears to be enough for them to understand why she made up these lies. Although the entire class is sympathetic to Woo-rim's plight, her confessional also comes off as a form of punishment for her lies. Also, since she had played games with Yeo-min regarding her affection towards him and had contributed to the false accusations of Yeo-min stealing money, this scene equally presents punishment for Woo-rim's treatment of our hero. In the end, Woo-rim purchases the sunglasses Yeo-min wanted for his mother because she realizes that she will only be his "number two" whereas Yeo-min's mother is his "number one." This scene also negates Yeo-min's mother's message to Yeo-min that she does not want the sunglasses. With Yeo-min receiving the sunglasses from Woo-rim with a voiceover that claims Yeo-min's philosophy as correct, mother's words are overruled by Yeo-min, the "masculinizing" hero.

The positioning of Woo-rim also contributes to When I Turned Nine's repositioning of patriarchy. Woo-rim has been lying to her new classmates that her father lives in America, from where he buys her many gifts. This is the secret that Yeo-min is aware of through Keum-bok's sleuthing. Yeo-min, as leader, asks Keum-bok to refrain from exposing this secret as a favor to him because he feels Woo-rim has her reasons for telling these lies and he doesn't want Keum-bok to embarrass her. Keum-bok, in the heat of anger and jealousy, does end up exposing Woo-rim's lies to the class. But Woo-rim does eventually fess up publicly on her own to her classmates in a horribly overly melodramatic scene. This confessional has the whole school crying because Woo-rim is a child of divorce and that appears to be enough for them to understand why she made up these lies. Although the entire class is sympathetic to Woo-rim's plight, her confessional also comes off as a form of punishment for her lies. Also, since she had played games with Yeo-min regarding her affection towards him and had contributed to the false accusations of Yeo-min stealing money, this scene equally presents punishment for Woo-rim's treatment of our hero. In the end, Woo-rim purchases the sunglasses Yeo-min wanted for his mother because she realizes that she will only be his "number two" whereas Yeo-min's mother is his "number one." This scene also negates Yeo-min's mother's message to Yeo-min that she does not want the sunglasses. With Yeo-min receiving the sunglasses from Woo-rim with a voiceover that claims Yeo-min's philosophy as correct, mother's words are overruled by Yeo-min, the "masculinizing" hero.

The masculinizing of our hero Yeo-min is different from the images of "remasculinizing" men Korean film scholar Kyung Hyun Kim finds in the Korean films of the late 80's and entire 90's. Yeo-min is never portrayed as pathetic, Yeo-min's plight is not fully centered around experiencing a trauma, and, rather than resist a collective identity, he directs a male horde surrounded by adoring females, each counter to the criteria Kim has noted in the male images of 'South Korea's New Wave.'(9) Whereas Sweet Sixties also refuses to remasculinize, it equally refuses to masculinize by privileging alternative masculinities against an astounding attack upon the very character who does attempt to masculinize, Jin-bong. Yet one week after Sweet Sixties, we find a film like When I Turned Nine eclipsing whatever progress was made re-imagining men. When I Turned Nine acquired around 130,000 Seoul admissions with a Seoul per screen average of roughly 4,800; whereas, Sweet Sixties only retrieved roughly 13,500 admissions and a per screen average of roughly 1,100.(10) Working off these numbers, it appears that Seoul audiences were warmer to Yeo-min's retro-take on masculinity than that of the elder new men.

However, there are signs in When I Turned Nine that cause me to be hesitant to claim it as a complete step backward from Sweet Sixties leap forward.(11) The signs are in the form of three characters, Yeo-min's father, Yeo-min's teacher, and a local disabled vendor. Concerning Yeo-min's father, I have mentioned before that he is portrayed as someone void of violence. In fact, it is Yeo-min's mother who is shown spanking Yeo-min's bare calves with a rod rather than Yeo-min's father. Also, Yeo-min's father is positioned against the local alcoholic as the obviously better man. Rather than beat his wife, Yeo-min's father comforts and consoles her. Yeo-min's father is only shown offering guidance supported through tenderness and a basic understanding of right and wrong, rather than through force. This is further reinforced through Yeo-min's reluctance to fight himself, only breaking into physical violence when his mother's honor is questioned or his loyal friends are threatened.

However, there are signs in When I Turned Nine that cause me to be hesitant to claim it as a complete step backward from Sweet Sixties leap forward.(11) The signs are in the form of three characters, Yeo-min's father, Yeo-min's teacher, and a local disabled vendor. Concerning Yeo-min's father, I have mentioned before that he is portrayed as someone void of violence. In fact, it is Yeo-min's mother who is shown spanking Yeo-min's bare calves with a rod rather than Yeo-min's father. Also, Yeo-min's father is positioned against the local alcoholic as the obviously better man. Rather than beat his wife, Yeo-min's father comforts and consoles her. Yeo-min's father is only shown offering guidance supported through tenderness and a basic understanding of right and wrong, rather than through force. This is further reinforced through Yeo-min's reluctance to fight himself, only breaking into physical violence when his mother's honor is questioned or his loyal friends are threatened.

The man exhibiting the most violence is Yeo-min's teacher, and his violence is not fully approved. He is shown going overboard when vigorously slapping Yeo-min after Yeo-min has been falsely accused of stealing Woo-rim's money. In this way, exerting one's male power through violence is shown as of limited necessity. Only the lowest men beat their wives, such as the alcoholic. And those who mis-use their violence are held suspect. The teacher's competence, and thus his legitimate authority over Yeo-min, is questioned when he mistakenly accuses Yeo-min of stealing and when he attempts to take credit for Yeo-min's artistic talent, only to make himself look silly in front of a superior.

And then we have the local disabled vendor, whom the children call "Mr. One-Arm", who challenges depictions of the Disabled in literature and film as metaphors for emasculinization. Mr. One-Arm, whose army jacket signifies that he lost his arm during the Korean War, is portrayed as a man respected in the community, a man who offers advice to the children that they respectfully accept. Even further confounding stereotypes, he is not the object of charity, but the subject, offering the children free popcorn. Mr. One-Arm's able-ness is further presented through his being one of the adults who come to rescue both Woo-rim and Yeo-min from the river incident, carrying Yeo-min to the hospital. By carrying our hero, Mr. One-Arm is by extension a hero himself. Placing Mr. One-Arm against, say, the character of Young-ho in Aimless Bullet (Yu Hyon-mok, 1961), a character who refused to marry his girlfriend since he felt he had lost his manhood in the war when he lost his ability to walk free of crutches, we can see the progressive push that exists within this character of Mr. One-Arm.

Yet, Mr. One-Arm is still positioned to reinforce patriarchal prominence since he can also be placed against another disabled character, Yeo-min's mother. Whereas Mr. One-Arm can fend for himself, Yeo-min's mother is shown as requiring her husband's and son's protection. Mr. One-Arm is welcomed into the camaraderie of male solidarity similar to Yeo-min's male friend Ki-jong.(12) Thus, this progressive portrayal of disabled Mr. One-Arm as an equal member of the fraternity is done at the expense of Yeo-min's disabled mother and her sisterhood.

Yet, Mr. One-Arm is still positioned to reinforce patriarchal prominence since he can also be placed against another disabled character, Yeo-min's mother. Whereas Mr. One-Arm can fend for himself, Yeo-min's mother is shown as requiring her husband's and son's protection. Mr. One-Arm is welcomed into the camaraderie of male solidarity similar to Yeo-min's male friend Ki-jong.(12) Thus, this progressive portrayal of disabled Mr. One-Arm as an equal member of the fraternity is done at the expense of Yeo-min's disabled mother and her sisterhood.

Although, When I Turned Nine is not a full rewinding return to definitions of masculinity from days past, two steps back to Sweet Sixties three steps forward, we still have the retrenchment towards a masculinity that is the opposite of liberation since it requires the control of others by the privileged position of men. With the drastic box office difference between these two films, along with the "unexpected"(13) awards for When I Turned Nine for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay (Lee Man-hee) and a Child Acting Award for the four principles (Lee Se-yeong, Kim Seok, Na Ah-hyun, and Kim Myung-jae) at the Chunsa Art Awards(14), it appears that the progressive masculinities of Sweet Sixties may well be forgotten in lieu of the regressive masculinities of When I Turned Nine.

ENDNOTES

As is the case with some South Korean DVDs, the subtitles can be questionable at times. When I have quoted from the subtitles in this essay, I have confirmed their general reliability from Korean language speakers, some of whom are native speakers and some of whom are second-language speakers. However, I do not have the resources available to fully crosscheck the subtitles of the entire film. I submit that such leaves my non-Korean-fluent self vulnerable to misinterpretations. However, first and foremost, all essays represent one's unique self interacting with a text, with notes on history, culture and politics that apply. Similarly, although I wish to thank Brian Darr for his helpful feedback, and Tom Giammarco, Kyu Hyun Kim, and Darcy Paquet for both their helpful feedback and occasional research assistance, all arguments, errors, and omissions should be seen as those of the author and no one else's.

(1) Lee Su-yeong had quite a busy year for such a young actress. She also had a starring role in the film Lovely Rivals (dir. Jang Gyu-sung), released in Seoul on November 17, 2004.

(1) Lee Su-yeong had quite a busy year for such a young actress. She also had a starring role in the film Lovely Rivals (dir. Jang Gyu-sung), released in Seoul on November 17, 2004.

(2) The Korean title roughly translates as "When Loneliness Writhes" or "When Loneliness Spasms" or, perhaps, with some liberties "When We Are Shaken By Loneliness". (Thanks to Tom Giammarco and Kyu Hyun Kim for clarifying that translation for me.) In my review of the film for Koreanfilm.org, I discuss the greater synergy of English-titling this film Sweet Sixties rather than the cringe- (or spasm?) inducing alternative title "Dances With Solitude."

(3) A veteran of many TV dramas and films, the 63 year old Kim passed away from pneumonia in 2005.

(4) This scene has an added layer of humor to the Korean viewer when witnessing Joong-bum singing so horribly. The actor, Park Young-gyu, is also a popular singer in South Korea. (I thank Kyu Hyun Kim for bringing Park's singing career to my attention.)

(5) Park Chung-hee held rule over South Korea from 1961 to 1979 after a military coup. According to Chungmoo Choi, the Motion Picture Law was revised several times under Park's regime, implementing severe censorship of defamation of the state in its fourth revision. (Chungmoo Choi, "Gender, Aestheticism, and Cultural Nationalism." In Im Kwon-taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema. (eds. David James and Kyung Hyun Kim), Detroit: Wayne State University Press, pp. 107-133.)

(6) Lee Seung-bok is a complicated figure in South Korean history. As the story goes, as a young child, Lee Seung-bok and his family were brutalized by North Koreans infiltrating South Korea in 1968 as retaliation for Lee yelling "I hate Communists!" In the early 1990's, a group of journalists challenged this entire story, but these journalists were sued for libel by the original journalists who reported the story for the South Korean newspaper, Chosun Ilbo. The Chosun Ilbo journalists won their libel case. Thus, as historian Kyu Hyun Kim pointed out to me, "Lee Seung-bok is not only a symbol of the Communist brutality, but also one of the extent to which the government can go to mobilize anti-Communism." (Email correspondence with author on 12/17/04 and personal conversation with author on 12/26/04.) By connecting and dis-connecting Jin-bong with this historical figure through the schoolboy's commentary, Jin-bong's anti-communist stance is brought further into question.

(7) Sweet Sixties was released in Seoul on March 19, 2004, while When I Turned Nine was released on March 26, 2004.

(7) Sweet Sixties was released in Seoul on March 19, 2004, while When I Turned Nine was released on March 26, 2004.

(8) This dialogue also provides back story, allowing the audience to infer that Yeo-min's mother acquired her eye-injury through a similar accident as the one that occurred here.

(9) Kyung Hyun Kim, The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004. My comments here should not be read as disagreement with Kim's arguments, since I concur with many of them. I am simply stating my choice to use "masculinizing" here rather than "remasculinizing" to differentiate When I Turned Nine's tactics from its predecessors.

(10) Statistics are based on information provided by Darcy Paquet on the Koreanfilm.org website (last viewed March 22, 2005).

(11) And conversely, Sweet Sixties tips its hat to patriarchy as well through its efforts to associate Jin-bong with femininity in order to discredit his authority. I am speaking of the fact that Jin-bong is revealed to have a fetish for women's underwear, a plot tactic used to humiliate him.

(12) When Yeo-min asked a favor to Keum-bok and another female character to keep Woo-rim's secret, Ki-jong asks Yeo-min why he doesn't ask him to keep the secret. Yeo-min says it's because he trusts him. This juxtaposition of trusting his male friend but not trusting his female friends clinches the theme of male solidarity. A theme further demonstrated through Ki-jong's act of loyalty to Yeo-min by beating up the weak class nerd who dared to accuse Yeo-min of stealing, who dared to not be a man like Yeo-min and Ki-jong.

(13) "When I Turned Nine Unexpected Winner of Chunsa Film Art Awards" available online at Han Cinema (The Korean Movie Database).

(14) South Korea has many movie awards ceremonies. Some argue the Grand Bell Awards held in the spring are the most prestigious, with its closest rival being the Blue Dragon Awards held in December. (See Darcy Paquet, "Film Awards Ceremonies in Korea") The Chunsa Art Awards were founded in 1990 by the Korean Film Director's Society and were named after Na Un-kyu, an actor/director from the silent film era whose most famous film is Arirang (1926).