The Making of a Korean Film Scholarly Tradition:

A Review of Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema

by Adam Hartzell

If you are going to publish the first scholarly work on Korean Film in the United States, it would make sense to center it around IM Kwon-Taek. He is closing in on his 100th film, his most recent film, Chihwaseon (2002), being number 97. His work spans over forty years of Korean cinema, starting in 1962 near the middle of what is considered "The Golden Age of Korean Cinema." Studying Im allows one to survey more than just one genre since he has done popular films, melodramas, action films, historical epics, and art films. When Im's Mandala (1981) won the grand prix at the 1981 Hawaii Film Festival, Im became the first Korean director to show on the festival circuit in Europe for some time, being asked to compete in the Berlin Film Festival. Later, Gilsottum (1986) would win an award at the Berlin Film Festival, KANG Soo-yeon would win Best Actress for her role in Surrogate Mother (1987) at Venice, and Come, Come, Come Upward (1989) would be awarded at Moscow. More recently, Chunhyang (2000) would become the first Korean film to be invited to compete at Cannes and was Korea's official selection for the Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award. In 2002, Im received what is perhaps the film world's highest honor, the prix de la mise en scene (best director award) at Cannes for Chihwaseon. Im isn't representative of all that is Korean film, but he is largely responsible for the present success of Korean film.

If you are going to publish the first scholarly work on Korean Film in the United States, it would make sense to center it around IM Kwon-Taek. He is closing in on his 100th film, his most recent film, Chihwaseon (2002), being number 97. His work spans over forty years of Korean cinema, starting in 1962 near the middle of what is considered "The Golden Age of Korean Cinema." Studying Im allows one to survey more than just one genre since he has done popular films, melodramas, action films, historical epics, and art films. When Im's Mandala (1981) won the grand prix at the 1981 Hawaii Film Festival, Im became the first Korean director to show on the festival circuit in Europe for some time, being asked to compete in the Berlin Film Festival. Later, Gilsottum (1986) would win an award at the Berlin Film Festival, KANG Soo-yeon would win Best Actress for her role in Surrogate Mother (1987) at Venice, and Come, Come, Come Upward (1989) would be awarded at Moscow. More recently, Chunhyang (2000) would become the first Korean film to be invited to compete at Cannes and was Korea's official selection for the Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award. In 2002, Im received what is perhaps the film world's highest honor, the prix de la mise en scene (best director award) at Cannes for Chihwaseon. Im isn't representative of all that is Korean film, but he is largely responsible for the present success of Korean film.

Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema edited by David James and Kyung Hyun Kim, came out of a retrospective on Im at the University of Southern California in the Fall of 1996. Although not "the first English-language scholarly book on South Korean cinema published outside of Korea" (pg. 9) as the preface of the book claims, (such should be credited to Hyangjin Lee, a Lecturer at the University of Sheffield, who published Contemporary Korean Cinema: Identity, Culture, Politics in England), it begins to fill the void in scholarly writings on Korean film.

Kyung Hyun Kim, an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine, starts off the collection with an overview of the history of Korean cinema, Im's life, and his oeuvre. What is unique about Im is that he was able to walk the diplomatic line throughout Korea's tumultuous history. No other director of his generation was able to accomplish such longevity. He started out not as a dreamer, but as a pragmatist. He was not hungry for art, but food. He needed to work to feed his family and he stumbled upon the film industry. His drive was making money, not art. Thus, he focused on low production costs and high output. In his first 10 years as a director, he averaged 5 films a year. In 1973, Im directed The Deserted Woman, a film he says represents his change in film-making direction. He was feeling degraded by the cheap films he was making and was becoming increasingly aware that he could not compete against American films, so he decided to begin making serious art films. Im arranged an agreement with his financiers that he would make successful films to help pay for his art films. After the huge surprise success of Sopyonje (1993), a film seemingly pre-destined for a huge loss that ended up grossing more than any film had before in Korea, Im has been given free reign to create whatever his new heart desires.

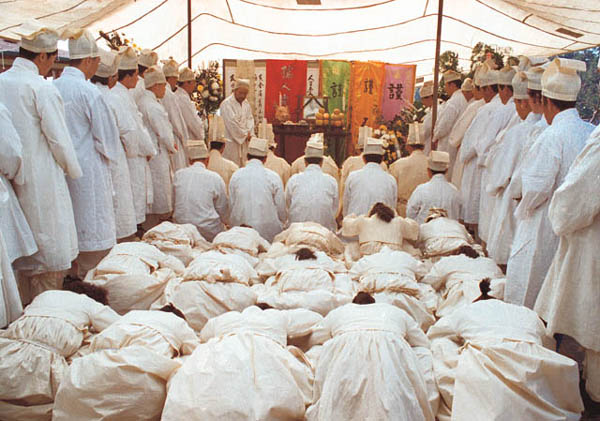

The films by Im that are discussed at length in the book are the following: Adada (1988), Come, Come, Come Upward (1989), Festival (1996, pictured left), Fly High, Run Far: Kaebyok (1991), The Genealogy (1978), Mandala (1980), Sopyonje, Surrogate Mother (1986), and The Taebaek Mountains (1991). (An Im filmography is included at the end of the book along with an appendix of significant moments in Korean history and Korean cinema history.) The articles included tackle Im's films from multiple interests. Of particular interest of many of the scholars was how Im utilizes the suffering of women's bodies as metaphors for Korea's traumatic history. Eunsun Cho, at the time a graduate student in the School of Cinema-Television at the University of Southern California, notes in her chapter, "The Female Body and Enunciation in Adada and Surrogate Mother," that these two films are rare in Im's oeuvre since they allow for moments when the women are permitted to resist the silence imposed upon them. Interestingly, since their bodies are used as metaphors, these characters resist and speak out through their bodies not their words. Similarly, Chungmoo Choi, an associate professor at the University of California, Irvine, in her chapter "The Politics of Gender Aestheticism and Cultural Nationalism in Sopyonje and The Genealogy," argues that these films demonstrate how "colonized Korean men attempted to respond to the deprivation of national identity and loss of masculinity by inflicting violence on colonized indigenous woman or onto the emasculated self" (pg. 109). Of particular note in this article is Choi's argument that Song-hwa was raped by Yu-bong following his blinding her through poison. I can not do Choi's argument justice in a few sentences, but a key aspect of the argument is Song-hwa's dress changing to "the time-honored fashion of a married woman" (pg. 108) soon after the blinding. Although Im, in the interview that closes the book, is translated to have said, "I argue that you should not see Sopyonje as a film that exploits women" (pg. 258), after reading Choi's argument, it is difficult not to read the scenes that follow the poisoning as evidence of an incestuous rape.

The films by Im that are discussed at length in the book are the following: Adada (1988), Come, Come, Come Upward (1989), Festival (1996, pictured left), Fly High, Run Far: Kaebyok (1991), The Genealogy (1978), Mandala (1980), Sopyonje, Surrogate Mother (1986), and The Taebaek Mountains (1991). (An Im filmography is included at the end of the book along with an appendix of significant moments in Korean history and Korean cinema history.) The articles included tackle Im's films from multiple interests. Of particular interest of many of the scholars was how Im utilizes the suffering of women's bodies as metaphors for Korea's traumatic history. Eunsun Cho, at the time a graduate student in the School of Cinema-Television at the University of Southern California, notes in her chapter, "The Female Body and Enunciation in Adada and Surrogate Mother," that these two films are rare in Im's oeuvre since they allow for moments when the women are permitted to resist the silence imposed upon them. Interestingly, since their bodies are used as metaphors, these characters resist and speak out through their bodies not their words. Similarly, Chungmoo Choi, an associate professor at the University of California, Irvine, in her chapter "The Politics of Gender Aestheticism and Cultural Nationalism in Sopyonje and The Genealogy," argues that these films demonstrate how "colonized Korean men attempted to respond to the deprivation of national identity and loss of masculinity by inflicting violence on colonized indigenous woman or onto the emasculated self" (pg. 109). Of particular note in this article is Choi's argument that Song-hwa was raped by Yu-bong following his blinding her through poison. I can not do Choi's argument justice in a few sentences, but a key aspect of the argument is Song-hwa's dress changing to "the time-honored fashion of a married woman" (pg. 108) soon after the blinding. Although Im, in the interview that closes the book, is translated to have said, "I argue that you should not see Sopyonje as a film that exploits women" (pg. 258), after reading Choi's argument, it is difficult not to read the scenes that follow the poisoning as evidence of an incestuous rape.

Kyung Hyun Kim's second article, "Is this How the War Is Remembered?: Deceptive Sex and the Re-masculinized Nation in The Taebaek Mountains," and Han Ju Kwak's article, "In Defense of Continuity: Discourses on Tradition and the Mother in Festival," both continue with this feminist critique of Im. (It is commendable, having brought Im in for this retrospective, that most of the scholars here have not held back in taking Im to task about the repetition in his films of rapes and scenes of women being abused that border on sado-masochistic, such as in Surrogate Mother. Im's insistence on this trope has continued on into Chunhyang which is a story that's mere choice to film by Im requires the further display of a woman suffering as Korea.) Kim argues that Im focuses on "abhorrent, illicit, and transgressive sexual encounters" (pg. 1998) in The Taebaek Mountains to make the crisis of the film the crisis of Korean men, which later justifies "the restoration of 'tradition' and order under a recharged masculinist identity" (pg. 199). Kwak, who at the time was a graduate student in the School of Cinema-Television at the University of Southern California, also looks at the repeal to "tradition" that Im presents in Festival. The utopian conclusion of the film "is a retrospective and closed one, made possible only on the basis of communal patriarchal values and the suppression of individual desires and differences, particularly female ones" (pg. 240).

Cho Hae Joang's and Julian Stringer's articles both look at Sopyonje (pictured right). Cho, a professor in the Department of Sociology at Yonsei University, addresses the Korean public's response to the success and artistic power of Sopyonje in her article "Sopyonje: Its Cultural and Historical Meaning." Through an overview of student essays and Korean critics' essays, Cho summarizes all the questions about "Koreanness", tradition, modernity, and post-modernity that Sopyonje sparked in the Korean populace. Julian Stringer, a lecturer in the Institute of Film Studies at the University of Nottingham, England, looks at his Western response to Im's choice to bring in non-diegetic sound during the final moment of Sopyonje in his article "Sopyonje and the Inner Domain of National Culture." For those of you, like me before I read this book, who don't know what "diegetic sound" means, let alone "non-diegetic sound," diegetic sound would be that which is coming from the characters/instruments on screen, that is, from within the frame; whereas non-diegetic sound would be that which could not possibly be coming from what's on screen, that is, from outside the frame. In the case of the music in Sopyonje, diegetic sound would be when Song-hwa is singing p'ansori for us and non-diegetic would be when the instrumental, "traditional" music enters in the final scene and the Song-hwa on the screen in front of us becomes mute as well as blind. Stringer found himself feeling cheated from experiencing the power of p'ansori by Im's choice to go from diegetic to non-diegetic music in the final scene. Stringer eventually comes to the conclusion that Im chose this direction to avoid commodifying the artform of p'ansori.

Cho Hae Joang's and Julian Stringer's articles both look at Sopyonje (pictured right). Cho, a professor in the Department of Sociology at Yonsei University, addresses the Korean public's response to the success and artistic power of Sopyonje in her article "Sopyonje: Its Cultural and Historical Meaning." Through an overview of student essays and Korean critics' essays, Cho summarizes all the questions about "Koreanness", tradition, modernity, and post-modernity that Sopyonje sparked in the Korean populace. Julian Stringer, a lecturer in the Institute of Film Studies at the University of Nottingham, England, looks at his Western response to Im's choice to bring in non-diegetic sound during the final moment of Sopyonje in his article "Sopyonje and the Inner Domain of National Culture." For those of you, like me before I read this book, who don't know what "diegetic sound" means, let alone "non-diegetic sound," diegetic sound would be that which is coming from the characters/instruments on screen, that is, from within the frame; whereas non-diegetic sound would be that which could not possibly be coming from what's on screen, that is, from outside the frame. In the case of the music in Sopyonje, diegetic sound would be when Song-hwa is singing p'ansori for us and non-diegetic would be when the instrumental, "traditional" music enters in the final scene and the Song-hwa on the screen in front of us becomes mute as well as blind. Stringer found himself feeling cheated from experiencing the power of p'ansori by Im's choice to go from diegetic to non-diegetic music in the final scene. Stringer eventually comes to the conclusion that Im chose this direction to avoid commodifying the artform of p'ansori.

Yi Hyoin, a lecturer on film theory and Korean film history at several universities in Korea, including Kyung Hee University, chose to address Fly High, Run Far: Kaebyok in his chapter, "Fly High, Run Far and Tonghak Ideology." After summarizing Tonghak ideology that all people are heaven, Tonghak's place in Korean history, and the Tonghak Rebellion which the movie is about, Yi addresses the controversy around the film, that is, both rightists and leftists were unhappy with it. Yi argues that the film is a critique of the left from a director that can be argued to be more left of center. Im wanted to show how any ideology followed to the extreme will cause problems regardless of that ideology.

David James, who teaches at the School of Cinema-Television at the University of Southern California, is featured in a chapter entitled, "Im Kwon-Taek: Korean National Cinema and Buddhism," of which an abbreviated version appeared in the Spring 2001 issue of Film Quarterly. James discusses Im's two films that relate to Buddhism, Mandala and Come, Come, Come Upward, noting how they both "explore the same question: What is socially at stake in the choice between a pure ascetic life in the mountains and a life of active participation in the world's affairs." It is argued that Im's concerns in these films are institutional Buddhism's times of unresponsiveness to the national social conditions of Korea.

Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema ends with an interview with Im. The point that is underscored throughout the interview is the fact, mentioned near the beginning of this review, that Im did not pursue film initially because of a dream or some political or artistic statement he wanted to make. He pursued film to meet life's basic needs, not the luxurious ones.

Interviewers: Film historians are interested in what has influenced you. When you were young, were there particular styles that inspired you?

Im Kwon-Taek: Growing up, I wasn't in the environment where I could watch many movies. I only began working in the film industry in order to survive during the postwar period. Once working in film, naturally I watched all the films that were imported. And I think that influences were there, but mostly I learned the craft directly from the production set. (pg. 261).

In this way, Im poses a challenge to our ways of thinking about the emergence of directors and their oeuvres. So many directors talk about their influences and an urge to create from their earliest beginnings. Im wasn't entering the film world based on some past artistic influence nor some existential anguish to create, the man just wanted to make sure he brought home the bulgogi. Only later did he start to create art, did he start thinking about representing Korea to the world and saving its traditions from itself.

To survive, Im had to walk a political tightrope along with the financial tightrope. The military dictatorships were never sympathetic to families with leftist backgrounds such as Im's. Ever cautious, Im held back the release of The Taebaek Mountains until a civilian president was in power. Yet, Im was able to present a rare sympathetic view of the Japanese after colonization in his film The Genealogy. Im may not have posed the stark challenges to Korea's government or people that many argue he should have, but, as Kim notes "He has exuded a spirit of endurance and tolerance, if not resistance, that far outweighs the complicity and compromises involved in the shaping of his career" (pg. 40).

Many have mis-analogized Im as the Kurosawa of Korea. I myself have been guilty of this. Others have compared Im to Mizoguchi, which isn't really accurate either. It is Kyung Hyun Kim, again, who has provided the truer analogy of Im: "He was Korea's Spielberg - but more versatile, radical, and profound than Spielberg ever dreamed of being" (pg. 40).